After seven essays in our Mapping Social Media series, we wanted to take a step back and evaluate our work so far. We thought a good way to do this would be to construct a list of the top 100 most popular social media platforms (a harder task than you might think!) and see what we could learn from it using the analytical framework we’ve developed over the course of this series. We also examined our analytical framework itself, comparing it to existing frameworks and exploring where it worked and where it fell short.

Top 100

Constructing a top 100 list wasn’t easy. There’s no official “registry” of website traffic that serves as a “league table” for social media. Instead, there’s a variety of tools used by the advertising industry to choose where to purchase ads. Some of these tools work by auditing website traffic logs; others track a panel of users to estimate traffic to different sites. These methods are not consistent across providers, and it’s therefore difficult to come up with a decisive ranking of the most visited websites, especially once you get beyond the most highly trafficked. Besides that, as we’ll discuss here, it’s not at all clear what websites should be considered “social media.”

For our initial data collection, we used a combination of SimilarWeb’s list of the top 100 social networks and online communities, Alexa’s list of the top 500 sites on the web, and Wikipedia’s list of social networking services. (The initial collection was done in November 2020.) Measurement sites like SimilarWeb and Alexa aren’t perfect tools for measuring popularity. They focus mostly on website traffic, which means they can be blind to mobile usage. However, the two services are complementary: Alexa uses a panel to measure what sites users visit, while SimilarWeb relies on “first-party direct measurement”—the logs maintained by website providers. We aren’t claiming this list is definitive or comprehensive, but we do believe it offers a rough picture of the most popular social media platforms worldwide.

As we compiled our list, it became clear that social is eating the world. Many, many websites and apps have some social features. This made deciding what to classify as social media difficult. Are dating sites like Tinder and Hinge social media? Are wikis like Wikipedia and Namu.wiki social media? What about content subscription sites like OnlyFans or Patreon? Our definition of a social media platform from the initial post in our series was: “a digital space that combines communicating or sharing media with aspects of social networking sites.” We think this definition still holds up, but must be sharpened to deal with the pervasiveness of social features.

To help us with line-drawing, we settled on a subjective test: is the platform in question more like “a site with social features” or is it “social first”? Consider The New York Times, which has a comment section on many of its online articles, or Amazon, which hosts customer reviews and discussions on product pages. We wouldn’t call The New York Times or Amazon a social media platform. They are, respectively, a news website with social features and an online retailer with social features. Same goes for Wikipedia—it’s a collaborative online encyclopedia with social features, not a social media platform. Dating sites were more difficult, but in the end, we decided that they were more akin to platforms like Uber which operate two-sided marketplaces—i.e., Tinder is a matchmaking platform with social features. Similarly, we decided that content subscription sites like OnlyFans, Patreon, and Substack are closer to being transaction platforms than platforms for sociality. (This could change if they achieve widespread adoption and add features like content aggregation. Today, these platforms are dominated by paid subscriptions to a small group of creators, but if they shift towards being dominated by content uploaded by the general public, it may make more sense to think of them as falling under creator logic.) Finally, a note about Zoom. In our chat logic essay we mentioned that we think chat logic applies to mediums other than text, like video and audio, specifically citing Zoom as an example. However, after reexamining our definition, we think Zoom is actually more of a utility, like the telephone, than a social media platform. In our thinking, Zoom is closer to Verizon or AT&T than Facebook or Twitter. It also doesn’t fit our definition of social media: the concept of a profile doesn’t make sense on Zoom, nor does articulating connections to other users.

The concept of a profile leads us to the other part of our definition that was highlighted while we compiled our list: danah boyd and Nicole Ellison’s requirement that social networking sites allow users to “construct a public or semi-public profile within a bounded system.” This principle helped us avoid having to include broad, diffuse ecosystems like the entire blogosphere in our analysis.

In the end, our definition and the lines we drew aren’t the “right” way to define social media. They are just one way that’s useful for our purposes.

After we determined a platform fit our definition of social media, we then categorized it by logic and by country. As you will see, we included logics that we have not yet written about for the series—some we were already actively researching, while others became apparent in the process of generating this list. When assigning a platform’s country, we assigned the country that was the source of the most visitors to the platform, as reported by Alexa.

Top 100 Analysis

The full top 100 list can be found at the end of this essay, with a downloadable version here. It is sorted in order of Alexa rank. (For platforms with popular mobile apps we estimated their Alexa rank by using monthly active user numbers.) We urge you to avoid over-focusing on any one platform’s rank, inclusion, or omission, though do feel free to ask about a platform you think was left out. As we said above, this is an attempt to offer a rough picture of the most popular social media platforms worldwide, not to provide a definitive or comprehensive ranking. We think the list is most useful for higher-level analysis, such as comparing the popularity of different logics or exploring the popularity of platforms by country.

Some brief observations:

First, the large number of non-U.S. platforms that were in the top 100 surprised us and was a healthy reminder of our U.S. centrism. They made up the majority of the list, comprising 61 of the top 100. However, maybe it shouldn’t be so surprising given, for example, that there are more than 900 million Chinese internet users who use popular Chinese social media platforms, including Sina Weibo, Douyin, and WeChat. Even platforms based in the U.S. that serve a large number of Americans sometimes serve more users from a different country. Take Quora: the country with the most visitors to Quora, according to Alexa, is India, which makes up 36 percent of traffic, followed by the U.S., with 28 percent of traffic.

We recognize that we’re not in a good position to evaluate the logics of foreign platforms, due to language and cultural barriers, so we’re reaching out to experts in Chinese, Russian, Korean, and Japanese social media for features on those communities. We expect to see some novel logics proposed to explain social media in those linguaspheres.

Next, we analyzed the popularity of different logics in our top 100. We assessed the popularity of each logic with this formula: take all the platforms that fall under a given logic and sum their points, where points are assigned in order, from most popular (by Alexa rank) to least popular. The most popular platform receives 100 points, the next most popular receives 99 points, all the way down to the least popular platform in the top 100, which receives 1 point. This allows us to capture a logic’s frequency in the top 100 while also incorporating the magnitude of each platform’s popularity. So, a logic with 10 platforms ranked towards the bottom of the top 100 won’t appear more popular than a logic that has five platforms that are all in the top 10. The results of that analysis follow:

Figure 1. Logics in order of popularity score

| Logic | Popularity Score |

| Creator | 1285 |

| Social Network | 978 |

| Chat | 958 |

| Subculture | 949 |

| Q&A | 461 |

| Chan | 140 |

| Social Bookmarking | 113 |

| Local | 62 |

| Enterprise Social Network | 46 |

| Alt-Tech | 42 |

| Crypto | 16 |

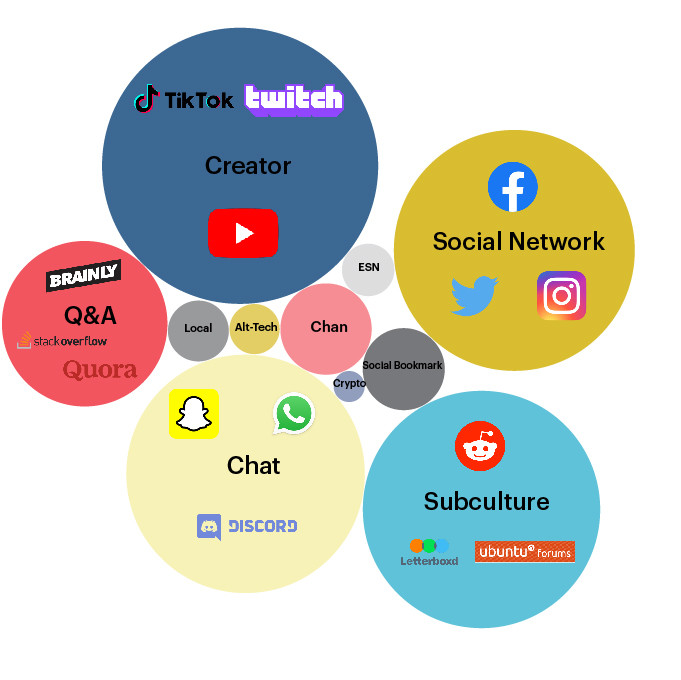

Figure 2. Logics sized by popularity score

The most popular logic was creator logic. We haven’t profiled creator logic yet so here’s a quick definition: creator logic platforms are for everyone and enable users to share a specific type of media (like video, livestreams, or art), in a one-to-many fashion. They are home to “creators,” people who consistently make content for the platform, often as a source of income. Some examples of creator logic are YouTube, TikTok, Twitch, and Wattpad. The popularity of creator logic and its relative lack of attention in comparison to social network logic suggests that journalists, scholars, and activists should direct more energy towards scrutinizing and understanding it.

Following creator logic in popularity were social network, chat, and subculture logic, respectively. The popularity of social network logic is no surprise. It covers dominant social networks like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and LinkedIn, social networks that are run by a single company, for the use of anyone for a variety of purposes, supported by advertising. Similarly, chat logic’s popularity isn’t surprising—chat platforms such as WhatsApp, Snapchat, and Discord boast some of the largest user numbers in the world and are hosting more and more of our social life online. Finally, subculture logic covers platforms that are organized around various subcultures. This logic is overwhelmingly populated by internet forums and their descendants—sites like Reddit, Steam Community, and Ubuntu Forums—but also includes sites like Ravelry, a social network for yarn enthusiasts, and Letterboxd, a social network for film lovers. Subculture logic, like creator logic, receives less attention than it deserves. One possible reason is that they are less popular among journalists, academics, and politicians, who mostly use Twitter or Facebook.

A surprise in the findings was the popularity of Q&A logic. It was the fifth most popular logic, occupying a middle tier between the dominant logics and the more niche logics. Q&A platforms are organized around users submitting questions and answers. Some are focused on a specific domain like Stack Overflow which serves mostly programmers, while others are more general-purpose like Quora. Q&A is a social media logic that is rarely in the spotlight, perhaps because it is particularly popular with communities that are less visible (programmers, students) and nations outside the U.S. (notably India). It clearly deserves more attention given its popularity and we will be profiling it in the future.

What logics didn’t make the top-100? Civic and decentralized. Their omission makes sense. Civic logic is an emerging idea that hasn’t received enough traction to make a list like this one yet. Also, civic logic platforms typically cater to smaller communities. As we put it in our piece about them, civic platforms “are likely limited to communities of a few dozen to a few thousand.” For decentralized platforms, the reasons for their lack of popularity are less inherent but no less significant. They face serious challenges to their adoption, specifically, they must “address their usability difficulties and overcome the massive network effects of centralized platforms.”

To supplement our popularity score analysis, we provide a bar chart with the raw frequency of each logic in the top 100 broken down by whether a platform was categorized as a U.S. platform or a non-U.S. platform. We also include a table with the average popularity scores for select logics.

Figure 3. Logic Frequency in Top 100

Figure 4. Logics in order of average popularity

| Logic | Average Popularity Score |

| Chat | 80 |

| Creator | 61 |

| Social Network | 61 |

| Q&A | 58 |

| Subculture | 33 |

The raw frequencies provide some useful context about the popularity results, highlighting differences between logics and nuances that aren’t clear from the popularity scores alone. For example, Figure 3 shows that there is a much higher number of subculture platforms outside the U.S. than in the U.S. We believe this could be due to Reddit’s popularity in the U.S., where it may function as a mega-forum, absorbing many standalone forums.

Additionally, looking at Figure 3 we see that subculture logic is first (by a large margin) in terms of raw frequency though it’s fourth in terms of popularity scores, implying that subculture logic is home to a broad array of platforms that cater to smaller userbases. Conversely, we can see that chat and social network logic have similar popularity scores to subculture logic but at much smaller raw frequencies, suggesting they are home to a less diverse array of platforms that host larger userbases.

To further investigate the differences in popularity concentration across logics, we calculated the average popularity for logics with at least eight platforms in the top 100 (see Figure 4). The frequency cutoff was eight, because the remaining logics had frequencies of five or less—small sample sizes that we believed were likely to give noisy results. The formula for a logic’s average popularity was: popularity score/frequency.

Chat logic has the highest average popularity at 80, followed by creator and social network logic at 61. On the low end is subculture logic at 33, with Q&A falling in between at 58. These findings make sense. Subculture logic is organized around discrete, insular communities, which have a ceiling on their potential userbase—there are only so many yarn enthusiasts. Conversely, chat, creator, and social network logic are typically organized around functionality that has a much higher potential userbase—hence Facebook’s mission to “connect the world.” Q&A reasonably falls somewhere in between.

Lastly, another interesting finding from the raw frequencies in Figure 3 is that the U.S. is home to the majority of low frequency logics. There are many possible explanations—we will offer two:

Social media is a space for experimentation in the U.S. and different logics continue to emerge as it matures. This is true in other countries and languages as well, and we are likely missing some of the more niche experiments due to our linguistic and cultural isolation. We would be grateful for pointers to social media in other countries that exemplify these less-common logics, or are introducing new logics entirely.

Political and cultural differences may play a role in the popularity of different social media logics. Take alt-tech logic, which covers platforms, like Gab, Parler, and TheDonald.win, that market themselves as bastions of free speech and mainly serve right-wing communities that have been deplatformed from mainstream platforms. Why could alt-tech be more likely to emerge in the U.S.? First, the U.S. receives disproportionate attention from the mainstream platforms because they are based in the U.S. and make most of their money in the U.S. This makes it more likely that fringe groups in the U.S. will be noticed, moderated, and kicked off. Second, political freedoms in the U.S. mean that fringe groups are allowed to create and maintain their own social media spaces. Third, the U.S. has a large population, making it more likely that a given U.S. platform will be featured in the top 100.

Five Axes Framework

Finally, we evaluated the five axes framework we’ve been using throughout the series to analyze platforms and form logics. Is it missing important factors that determine the nature of a social media platform? Are there existing frameworks that we should use instead? We found that most previous efforts to formulate an analytical framework for social media focused on only one or two of our axes; in particular, many efforts focused on the role of affordances. For example, Borgatti et al.’s “What’s different about social media networks? A framework and research agenda” lays out a framework for analyzing social media using social network analysis methods and theory. Essentially, the paper is an in-depth exploration of how affordances affect the dynamics and experience of a platform. This focus on affordances was common among the frameworks we reviewed.

However, one work did stand out: José van Dijck’s “A Critical History of Social Media.” It’s an excellent book that we highly recommend to anyone studying social media. In it, van Dijck formulates an illuminating and insightful analytical framework for social media. The framework presented is a combination of Bruno Latour’s actor-network theory, political economy, and other elements that focus on culture and norms. Platforms are analyzed as “microsystems,” which together make up an “ecosystem” of social media. Microsystems are approached in two ways: as “techno-cultural constructs” and as “socioeconomic structures.” Approaching microsystems as techno-cultural constructs means analyzing them in terms of technology, users, and content. Approaching them as socioeconomic structures means analyzing them in terms of ownership, governance, and business models. These six elements—technology, users, content, ownership, governance, and business models—are used to “disassemble” or analyze platforms.

The six elements used to disassemble platforms are similar to our five axes framework. However, van Dijck situates her framework in existing scholarship and explains why it is necessary, something we haven’t done. Therefore we considered adopting van Dijck’s framework in place of ours. However, there are some important differences between our approaches that led us to settle on revising our framework to incorporate the aspects of van Dijck’s framework that we think are useful.

As a result, our revised axes are:

- Technology

- Business Model

- Ownership

- Governance

- Affordances

- Stakeholders

What stayed the same? Our technology and affordances axes. van Dijck’s technology element is too detailed for our purposes and leaves out data storage, a key part of our analysis. Additionally, we prefer using our affordances axis to capture a number of design components (such as content, interface, and defaults) that van Dijck includes under her technology element.

What changed? van Dijck’s business model element and our revenue model axis are essentially identical but we decided to take the label of business model, as it’s clearer and grounded in existing scholarship. Next, we replaced our ideology axis with van Dijck’s ownership element. Ownership refers to a platform’s ownership status and structure; for example, “whether a platform is ... publicly governed, community based, nonprofit based, or corporately owned.” This is less ambiguous than our ideology axis, covers essentially the same thing, and places us squarely in the tradition of political economy. Similarly, we revised our definition of governance to be more expansive, taking van Dijck’s definition: “how, through what mechanisms, communication and data traffic are managed.” This doesn’t change our analysis much but it enables us to include technology and design decisions under our governance axis (which currently focuses on content moderation). Finally, we added a stakeholders axis that builds on van Dijck’s “users” element. van Dijck defines her users element as “explicit user responses to specific platform changes” that “embod[y] part of a negotiation process between platform owners and users to control the conditions for information exchange.” A good example is the recent boycott of Facebook by brands and celebrities in response to Facebook’s actions in the wake of George Floyd’s killing. We agree that who uses a platform, how they use it, and why has a great deal to do with its logic; for example, the way LinkedIn largely avoids harassment in contrast to Twitter and Facebook has a great deal to do with users, who are jobseeking and therefore (presumably) on their best behavior. However, the power of users to shape and influence platforms is perhaps less significant than van Dijck believes—platforms deal with their idealized user as much as they deal with real users. Additionally, there are other external stakeholders that may hold more sway than users. Governments, activists, and NGOs are often more likely to affect platform changes than a group of disaffected users. That’s why we broadened van Dijck’s users element to encompass the role of a variety of external stakeholders in shaping and influencing platforms.

Conclusion

As we said above, we do not claim our top 100 list is definitive or comprehensive so any findings derived from it should be treated with caution. Even so, we think the results demonstrate the benefits of combining an empirical approach with a rich theoretical perspective when studying social media. We hope our formulation of a definition and analytical framework is valuable and inspires further attempts to, as van Dijck puts it, “disassemble” and “reassemble” social media.

The findings that stick with us are: (1) social is eating the world; (2) social is global; and (3) social is much more than Facebook and Twitter. These findings get at the core of why we undertook this mapping project in the first place:

“Because Facebook and Twitter are so prominent and are so widely amplified by mainstream media, we tend to assume that all social media operate in the same way and suffer from the same problems.”

To move past the problems of today’s social media we need to overcome those assumptions and their associated myths and reach a more sophisticated understanding of the topic. The diversity of social media is clear, as are the possibilities, when we reject U.S. and Facebook centrism and strive for more complex thinking about the domain.

| Name | Logic | Popularity Score | Country |

| YouTube | Creator | 100 | U.S. |

| Social Network | 99 | U.S. | |

| Chat | 98 | India | |

| FB Messenger | Chat | 97 | U.S. |

| Chat | 96 | China | |

| Social Network | 95 | U.S. | |

| TikTok | Creator | 94 | U.S. |

| Chat | 93 | China | |

| Douyin | Creator | 92 | China |

| Sina Weibo | Social Network | 91 | China |

| Snapchat | Chat | 90 | U.S. |

| Subculture | 89 | U.S. | |

| Social Bookmarking | 88 | U.S. | |

| Telegram | Chat | 87 | India |

| Social Network | 86 | U.S. | |

| Quora | Q&A | 85 | India |

| Social Network | 84 | U.S. | |

| Imgur | Creator | 83 | U.S. |

| Line | Chat | 82 | Japan |

| imo | Chat | 81 | China |

| Brainly | Q&A | 80 | U.S. |

| douban.com | Social Network | 79 | China |

| Yy.com | Creator | 78 | China |

| Twitch | Creator | 77 | U.S. |

| VK | Social Network | 76 | Russia |

| Babytree.com | Subculture | 75 | China |

| Discord | Chat | 74 | U.S. |

| Likee | Creator | 73 | China |

| Slack | Chat | 72 | U.S. |

| Wattpad.com | Creator | 71 | India |

| csdn.net | Q&A | 70 | China |

| zhanqi.tv | Creator | 69 | China |

| tianya.cn | Subculture | 68 | China |

| ok.ru | Social Network | 67 | Russia |

| zalo.me | Chat | 66 | Vietnam |

| Stack Overflow | Q&A | 65 | U.S. |

| DeviantArt | Subculture | 64 | U.S. |

| VSCO | Creator | 63 | U.S. |

| NextDoor | Local | 62 | U.S. |

| aparat.com | Creator | 61 | Iran |

| medium.com | Creator | 60 | U.S. |

| Pixnet.net | Social Network | 59 | Taiwan |

| cnblogs.com | Subculture | 58 | China |

| Tumblr | Social Network | 57 | U.S. |

| 6.cn | Creator | 56 | China |

| Bilibili.com | Subculture | 55 | China |

| stackexchange.com | Q&A | 54 | U.S. |

| Tradingview.com | Subculture | 53 | U.S. |

| slideshare.net | Creator | 52 | India |

| zhihu.com | Q&A | 51 | China |

| Behance.net | Creator | 50 | India |

| nicovideo.jp | Subculture | 49 | Japan |

| Steamcommunity.com | Subculture | 48 | U.S. |

| kakao.com | Social Network | 47 | Korea |

| ameblo.jp | Creator | 46 | Japan |

| 9gag.com | Chan | 45 | Germany |

| dcard.tw | Subculture | 44 | Taiwan |

| namasha.com | Creator | 43 | Iran |

| LiveJournal | Social Network | 42 | Russia |

| ninisite.com | Subculture | 41 | Iran |

| 4chan | Chan | 40 | U.S. |

| flickr.com | Creator | 39 | U.S. |

| ptt.cc | Subculture | 38 | Taiwan |

| kizlarsoruyor.com | Q&A | 37 | Turkey |

| 5ch.net | Chan | 36 | Japan |

| hatenablog.com | Creator | 35 | Japan |

| renren.com | Social Network | 34 | China |

| plurk.com | Social Network | 33 | India |

| eyny.com | Subculture | 32 | Taiwan |

| lihkg.com | Subculture | 31 | Hong Kong |

| xing.com | Subculture | 30 | Germany |

| miaopai.com | Creator | 29 | China |

| dxy.cn | Subculture | 28 | China |

| FetLife | Subculture | 27 | U.S. |

| yammer.com | Enterprise Social Network | 26 | U.S. |

| weheartit.com | Social Bookmarking | 25 | India |

| Parler | Alt-Tech | 24 | U.S. |

| letterboxd.com | Subculture | 23 | U.S. |

| Omegle | Chat | 22 | U.S. |

| wykop.pl | Subculture | 21 | Poland |

| workplace.com | Enterprise Social Network | 20 | U.S. |

| ask.fm | Q&A | 19 | Egypt |

| Taringa! | Subculture | 18 | Argentina |

| Mixi | Social Network | 17 | Japan |

| DLive | Crypto | 16 | U.S. |

| MeWe | Alt-Tech | 15 | U.S. |

| exblog.jp | Creator | 14 | Japan |

| 2chan.net | Chan | 13 | Japan |

| skyrock.com | Social Network | 12 | France |

| mydigit.cn | Subculture | 11 | China |

| NewGrounds | Subculture | 10 | U.S. |

| nnmclub.to | Subculture | 9 | Netherlands |

| Hacker News | Subculture | 8 | U.S. |

| Fark | Subculture | 7 | U.S. |

| fuliba2020.net | Chan | 6 | China |

| computerbase.de | Subculture | 5 | Germany |

| instiz.net | Subculture | 4 | Korea |

| Gab | Alt-Tech | 3 | U.S. |

| skoob.com.br | Subculture | 2 | Brazil |

| Blind | Subculture | 1 | U.S. |

Chand Rajendra-Nicolucci is a research fellow at the Knight Institute.

Ethan Zuckerman is associate professor of public policy, information and communication at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, director of the Initiative on Digital Public Infrastructure, and was the 2020-2021 visiting research scholar at the Knight Institute.