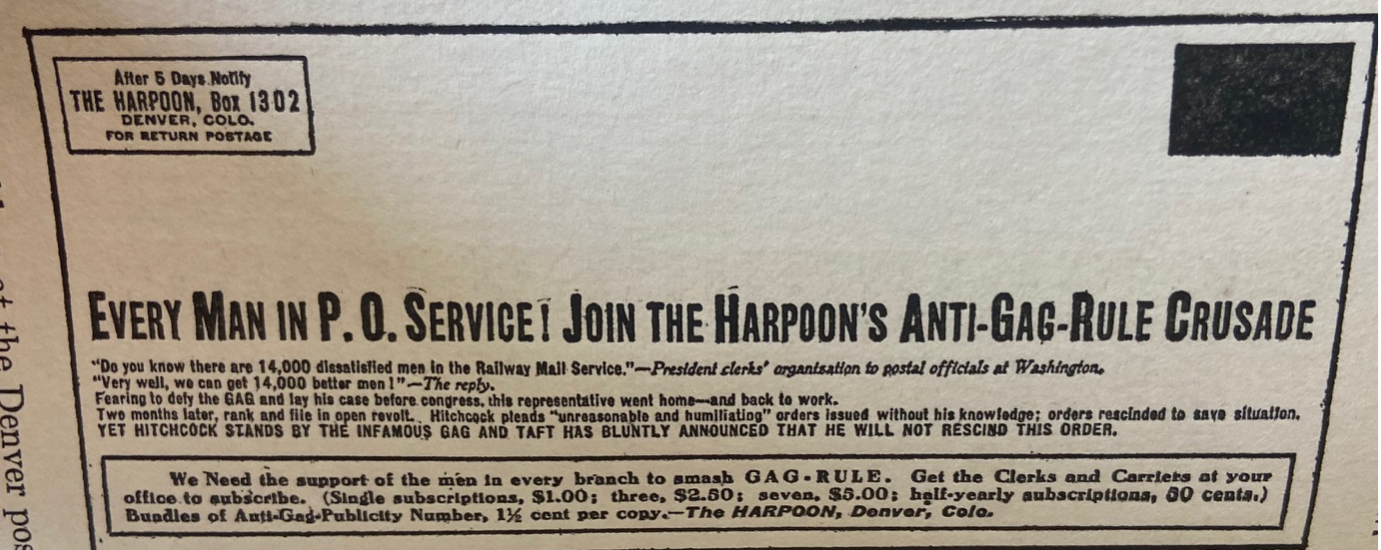

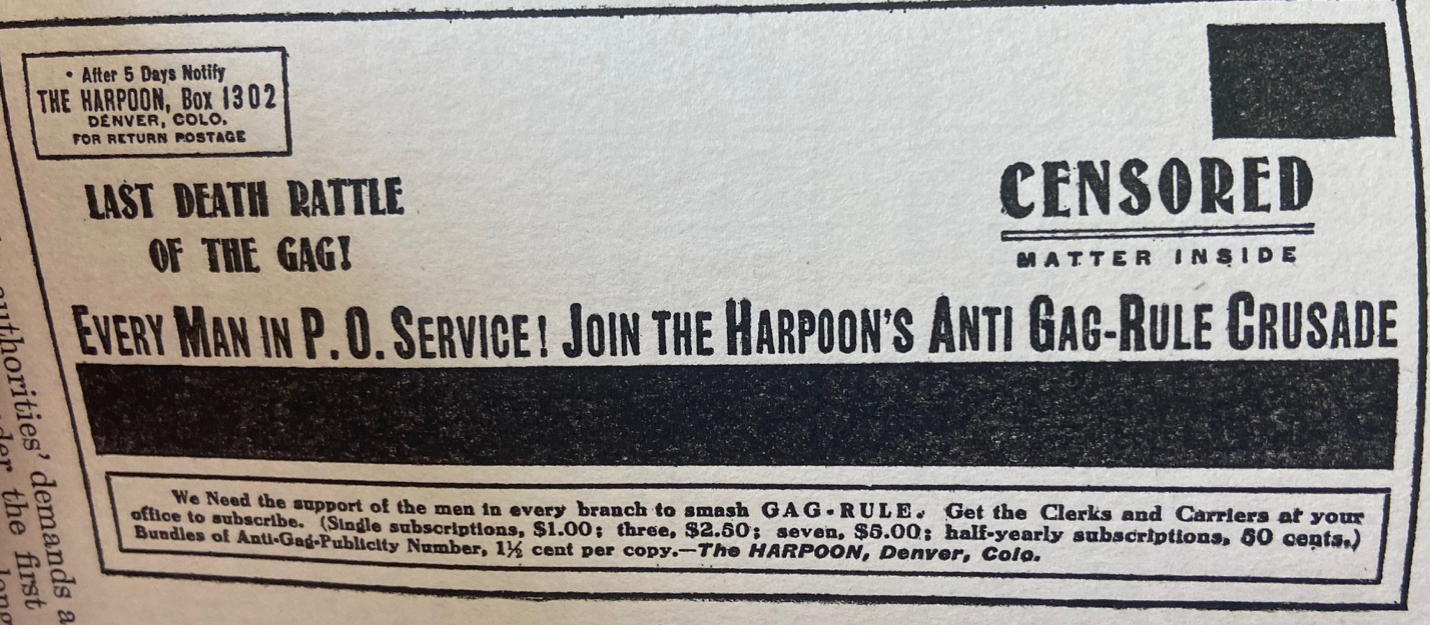

In 1909, Urban Walter, a 28-year-old mail clerk, founded a small magazine with large ambitions. According to its masthead, the Harpoon was “a magazine that hurts.” It was founded in pursuit of one goal: to oppose the Post Office Department’s imposition of a “gag order” on any discussion of the train wrecks that killed scores of railway mail clerks annually and maimed many hundreds more. These gag orders, first promulgated by the Postmaster General in the late 19th century, and later expanded by executive orders issued by Theodore Roosevelt and William Taft, prohibited civil servants from petitioning or giving information to Congress, or advocating for improved pay or working conditions except through their departmental head. The Harpoon defied the order, promising to give the “fullest publicity” the dangerous conditions, physical and organizational, of the work.

Walter was frequently ill with respiratory issues, exacerbated by moldy mailbags and the dusty, lamplit conditions on the mail car. To explain why he spent his precious “lay-off” time in a small print shop in Phoenix, Arizona, Walter invoked the highest of constitutional ideals. “No public official is great enough to take away the guaranteed rights of American citizenship,” Walter explained. “The very constitutional rights” of “lesser public servants” were abrogated by an order that, under penalty of swift removal, prohibited a clerk from discussing his working conditions publicly and from complaining to Congress. Under what Walter saw as the pretext of maintaining “efficiency of service,” postal officials had robbed 15,000 railway postal workers of their right to speech and right to petition the government. In so doing, officials had also undermined the public good, by keeping Americans ignorant of the conditions under which their mail was delivered.

Urban Walter and the railway postal clerks who read and wrote for the Harpoon understood their fight for speech rights not in individualistic and expressive terms, but as a precondition for public accountability. Because of the transient, hidden nature of railway postal work, disclosure of the clerk’s working conditions was the public’s window into a job that also bore upon public safety. In 1909 alone, 27 railway mail workers were killed, 98 “seriously injured,” and 617 “slightly injured”—the highest number of deaths on record. Under Walter’s framing, the disclosure of dangerous working conditions implicated the “public good,” and not just the narrow interests of an individual worker.

At the same time, Walter and other railway postal workers saw these gag orders not as a blunt instrument of “efficiency,” but as an explicitly anti-union tactic designed to forestall the organization of an effective railway postal workers organization. Walter and other postal clerks fought to affiliate with the American Federation of Labor (AFL) through a breakaway faction of the Department-dominated Railway Mail Association (RMA). Many of those clerks were fired—dismissed for the “good of the service,” or because of their “pernicious activity.” Walter was one such worker. He sent Postmaster General Frank Hitchcock “an advance copy” of Harpoon’s first issue, instructing the economy-minded Taft appointee to “carefully peruse” the enclosure. In response, the Department’s informed him that his (untendered) resignation had been accepted. A clerk sent Walter a dead rat that he had found inside the drinking water of his car. A photo of the rat appeared in the Harpoon. The clerk was also fired. Other supporters of the magazine were threatened with dismissal—which intensified the newspaper’s support, producing a culture of insubordination in defiance of executive orders and in support of public employee speech.

A fired worker is dangerous, a fired worker with access to a printing press doubly so. No longer facing a gag, Walter devoted himself full-time to the job of gadfly publisher and labor advocate. Less than three years after the Harpoon’s founding, Walter himself appeared before Congress, urging the passage of a single bill that would repeal the gag orders and protect the organizing rights of postal workers—speech goals that were to be linked legislatively as they had been in Walter’s protest. In his testimony, Walter accused the Postmaster General of “misinforming the committee” outright on the age and safety of mail cars. Because clerks were prohibited from disclosing information to Congress, legislators remained ignorant. The committee was thus forced to confront its own powerlessness in the face of executive branch orders. As Samuel Gompers, the president of the AFL, was quick to observe, a decade of executive orders prohibiting federal employees from disclosing information to Congress “may just as well have been an inhibition to the Members of Congress … to ask for this information.”

With the institutional prerogatives of Congress and the material interests of organized aligned, the Lloyd-La Follette Act became law in 1912. The Act had four discrete provisions: “no person in the classified service of the United States shall be removed therefrom except for such cause as will promote the efficiency of said service”; a requirement that a fired civil servant be furnished with written charges and an opportunity for responding to them; protection against removal or retaliation for postal employees who belonged to societies, associations, or unions—so long as the organization imposed no “duty to strike”; finally, the Act affirmed civil servants’ right to petition Congress “either individually or collective” and to “furnish information to either House of Congress, or to a committee or Member thereof.” This latter provision constituted the first statutory protection for whistleblowers, later expanded by the Civil Service Reform Act of 1978 and the Whistleblower Protection Act of 1989.

But taken together, the Act’s provisions reflected organized labor’s view of the value of speech, Congressional oversight, and government service. While not requiring the examination of witnesses or a trial-type hearing, the Act still afforded new tenure protections for hundreds of thousands of government employees, moving government employment firmly away from an at-will model. Though paltry in comparison to later procedural safeguards, the requirement that government employees be provided with reasons for their dismissal and an opportunity to contest those reasons nonetheless reflected both a skeptical view toward the state and an adversarial view toward management. This due-process culture that defined private sector organizational governance in the second half of the 20th century was first imagined, in thin form, by civil servants and their labor advocates. And, of course, the affirmation of the right of postal employees to unionize—also subtly suggested by the right to petition Congress collectively—is testament to labor’s vision of public employee speech. In the early 20th century, a person may have possessed no constitutional right to be a postal worker, to paraphrase Oliver Wendell Holmes. But once he became one, Congress created a modest protection for him to air his dissatisfactions—and to belong to worker organizations that incubated and emboldened complaint.

The purpose of this essay is twofold: I seek to contextualize the passage of the Lloyd-La Follette Act, a curiously understudied piece of legislation. In so doing, I situate the Act within the history of the civil service and the development of an increasingly powerful presidency. Secondly, I highlight the labor origins of whistleblowing. The AFL was an early opponent of the gag orders that silenced civil servants. It was responsible for drafting the Act itself, and even approved its only substantial amendment—a prohibition on membership in unions that required a strike. Institutionally, it was a beneficiary of the law as tens of thousands of postal workers joined unions that affiliated the AFL in the latter half of the 1910s. The labor history of the Act has been obscured by its modern-day admirers, who view it primarily as an embodiment of the separation of powers. Understanding this earlier history of struggle for speech in the federal workforce can help scholars and citizens appreciate the role that labor organizations have played in safeguarding core democratic values like transparency and accountability.

Despite its significance to the history of the civil service and democratic accountability, the Lloyd-La Follette Act is surprisingly understudied by historians. Scholars of American political development that have studied the Act and its politics have understood it largely in terms of what it revealed about the relationship between Congress and the executive branch for control of the administrative state. Little attention has been paid to the underlying speech-related grievances of gagged civil servants. Part of this lacuna lies in the fact that labor historians, as a rule, have tended to focus on the private sector at the expense of the public—particularly in studies of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. But even studies of public sector unionism, like Joseph Slater’s Public Workers, begins with a historiographical lament at the marginalization of public employees within labor history before moving swiftly to the Boston police strike of 1919. Attention to the history of labor agitation within the railway mail service reveals the centrality of public employee speech and petition rights to the overall political vision of the AFL at the turn of the century. The absence of this history is especially ironic given its proximity to the scholarly foundations of labor history itself. In 1913, John Commons, the progressive Wisconsin economist, labor historian, and advisor to Sen. Robert M. La Follette, asked. “Should public employees organize as trade unions?” Yes, he answered, provided those organizations do not strike or maintain a closed shop—in other words, the organizational arrangements secured by the La Follette Act.

Legal historian Laura Weinrib has recently argued that the labor movement has played a neglected role in the development of civil liberties consciousness. Civil liberties, and especially the right to speech, were linked to a “right to agitation”—an economically redistributive vision that “sought to counter the consolidation of capital with organized power of their own.” Weinrib’s study has shaped my own, particularly her focus on the free speech commitments of the political left in the years before the First World War. The quest for civil servant speech—a right that labor partisans framed as constitutional, rejecting any distinction between rights and privileges or public and private employment—was part and parcel of labor’s vision of the First Amendment as a weapon of the weak against the powerful in the class war. By speaking and organizing without fear of reprisal, organized government employees could also enlist noncombatants into the fight as Americans might also come to understand their own health, safety, or timely receipt of the mails as implicated by conditions within the railway mail service. This labor history of public employee speech sensitizes us to organized labor’s role in envisioning, expressing, and safeguarding the public’s right to hear information that bears on matters of public concern.

The ideas and language ultimately enshrined in the Lloyd-La Follette Act were developed in response to the constitutional interpretation implied by a decade of gag orders and directives from the Postmaster General. The railway mail service of the early 20th century sheds light on scholarly debates on “administrative constitutionalism,” or the ways that agency officials implement and interpret constitutional rules and norms. The Post Office has long been recognized as a site where officials exercised broad authority over policies with constitutional dimensions—such as suppression of abolitionist literature and a “virtually unreviewable” discretion to censor “obscene” materials. Regulation of speech by postmasters and postal inspectors—in other words, administrative censorship—was pervasive well into the 20th century. Working conditions within the postal service—an instance of a bureaucracy’s “internal rules,” to use Mashaw’s formulation—reveals the Postal Department’s power in attempting to determine the meaning of speech rights in practice. With no input from courts, advocacy by railway mail clerks and their allies in the AFL also refashioned ideas about speech, due process, and separation of powers in the early 20th century.

The Lloyd-La Follette Act also represented a vindication of Congressional prerogative. The history of the gag orders issued under such self-consciously “strong” presidencies as Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft illustrates the perils of presidentialism. Indeed, an important goal of the orders was to maintain “tranquility” in the government’s relationship with railway companies by keeping the public ignorant. Civil service unions have furthered democratic accountability by protecting workers who transmit information to Congress. The twinned history of speech and labor rights suggests that a unionized civil service can serve as a check on presidential power. The flip side of this coin is that a diminution of labor rights and speech rights within the civil service redounds to the benefit of the executive at the expense of democracy.

I begin by sketching the relationship between civil service reform and organized labor in the late 19th century. Reform of the spoils system reshaped the postal service more than any other division of the federal bureaucracy, and by the late 19th century the Railway Mail Service (RMS) was the most important and prestigious branch within the postal system. It was also the most dangerous, spurring clerks to invigorate worker organizations and, eventually to attempt to affiliate with the AFL. I then turn to the promulgation of agency and executive gag orders intended to suppress the dissemination of grievance, prevent disclosure of information to Congress, and, eventually, to thwart union organizing amongst the clerks. Next, I examine the organized response to the gag orders—as well as the Postal Department’s weaponization of its bureaucracy to ferret out and fire dissident clerks—a move that backfired, resulting in still more unrest and publicity. Finally, I examine Congressional support for the speech rights of postal workers, which culminated in the passage of the Lloyd-La Follette Act, legislation that braided together the interests of railway mail clerks, organized labor, and Congress itself.

Organizing and the Civil Service

The passage of the Pendleton Civil Service Act of 1883 sought to destroy the spoils system. In the 19th century, the Post Office stood for spoils itself, as undelivered mail bags had become an emblem of government incompetence that inconvenienced business and everyday Americans alike. “No party can hope to manage the patronage of this Government in its present magnitude and maintain itself before the people,” one New York senator explained in support of reform. “The people demand efficiency in the officers. They only ask of the Post-Office Department that it shall take their mails and that it shall deliver them in the least possible time with the fewest possible mistakes.” The Act introduced “merit principles” into the federal civil service by requiring “open, competitive examinations” to determine the “fitness” of job seekers, forbade assessments, and by offering a degree of job protection for civil servants by forbidding their dismissal or demotion on explicitly political grounds. The Act had been long demanded by cosmopolitan reformers, usually Republicans, jealous of the bureaucratic standards recently set in Britain, France, and Prussia. For these reformers, the merit system meant progress, and patronage, provincialism.

As more positions fell within the purview of the law, civil service reform politicized federal service in new ways. The law allowed bureau and division chiefs—political appointments, all—to hire whomever they wanted for positions above the classified service for which tests were required. Patronage was thus transferred from the rank-and-file of the bureaucracy toward the top. In short, the Act enshrined merit for the crew and patronage for the few, concentrating political, social, and economic power atop bureaucracies, adding an additional political dimension to the class resentments that regularly inhere to working life, especially when the work was dangerous. The turn of the century contest over the speech rights of civil servants unfolded within the unsettled context of civil service reform, which contained contradictory impulses: an urge toward efficiency and centralization, and a drive toward independence and professionalism. Like the theory of executive power that gave rise to the gag rule, civil service reform was undertaken to improve efficiency and eliminate “mischief in the service.” But a professionalized civil service also reshaped the mental horizons of workers. By stabilizing federal employment, civil service reform allowed workers to imagine their working life unfolding over decades rather than over a single administration. It was easier for government employees to organize as workers, rather than as partisans, under a civil service system. In this way, civil service reform valorized meritorious labor in much the same way as contemporary craft unionism.

The passage of the Pendleton Act initially swelled the ranks of the Knights of Labor, which consistently advocated for the inclusion of more federal positions under the purview of the classified civil service. The organization also lobbied for member interests before Congress, making explicit the ways in which reform politicized federal employment as a class struggle fought on a terrain of separated powers. For example, though “laborers, workmen, and mechanics” in federal government had been covered by the eight-hour law since 1868, the Post Office Department had ruled that letter carriers were not covered by the law. After local organizations of letter carriers affiliated with the Knights, the organization drafted and lobbied Congress for a bill that would, 20 years after the eight-hour law went into effect, finally bring letter carriers under its ambit.

If Congress acted as a friend to labor, the executive eagerly embraced the role of management. The Post Office opposed the new law and refused to enforce it, citing “much concern and annoyance.” Under the Department’s interpretation, an eight-hour law translated into a 56-hour week. Since carriers did not work Sundays, this meant that a carrier needed to work more than nine hours a day to be eligible for overtime pay. Aaron Post, an aptly named letter carrier in Salt Lake City, sued in the U.S. Court of Claims in a test case arranged by the Knights-affiliated National Association of Letter Carriers. Upon appeal, the Supreme Court issued a judgment in favor of the letter carrier, observing that “the statute was manifestly one for the benefit of the carriers, and it does not lie in the mouth of the government to contend that the employment in question was not extra service.”

The end of patronage divorced the employment interests of federal employees from those of their appointee superiors, who did not necessarily share the same partisan affiliation. But it did not take politics out of federal work. Newly organized and professionalized postal workers continued to find sympathetic patrons in Congress, which had, since the earliest days of the Republic, competed with presidents over control of public administration.

Mail by Rail

The Railway Mail Service became part of the civil service in 1889. Given Republican political dominance in the postbellum decades, most railway mail clerks were Republican, many of them Union veterans. Even after classification, its partisan cast remained. The work of a railway mail clerk was intellectually and physically demanding. Experience—even if initially acquired by patronage—was required to sort and deliver the mail by train.

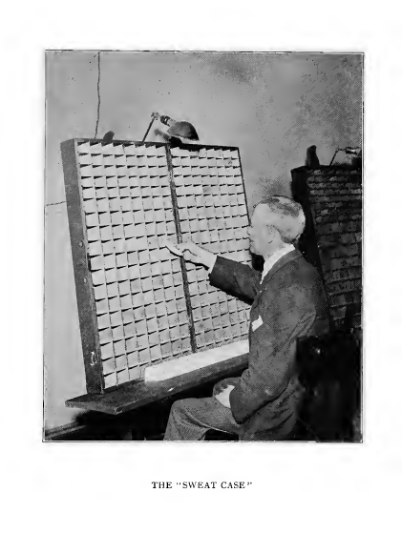

The work of a railway mail clerk was hard. Clerks had to perform prodigious feats of memorization—committing themselves to thousands of addresses, as well as the train routes that connected them. The civil service examination for the position of entry level clerk tested spelling, geography, arithmetic, penmanship, and letter writing. These were not especially technical skills. A high score on this exam was only the first, and easiest step. Once a vacancy occurred, the Civil Service Commission selected a name from the three highest in the examination pool where the vacancy existed (the rules required that a clerk live near the line where he might work). The individual was then designated as a substitute clerk, and given a bundle of documents to study: postal regulations, a map, a schedule of mail trains, a “scheme book” designating railway junctions, stations, post offices, active, parallel, and discontinued lines. He was then tested on his knowledge of this material through a written examination and a “case” examination—named for the portable wooden case in which it was administered. The latter inspired a particular sort of fear because it demanded instant recall and served as the basis of both entrance into the service and promotion. The purpose of the case examination was to evaluate a candidate’s skill in accurately and quickly routing mail on his line—there was, after all, no time to look up the best route for each piece of mail while the train was running. He was judged to have passed if he “threw” 99% of the examination cards correctly into the pigeonholes corresponding with various railway junctions and post offices. “Many clerks carry in their mind and at their finger ends 5,000 to 10,000 post offices, comprising several States and the schedules of hundreds of trains,” in the words of one admiring account. If a clerk passed these examinations, he was appointed to the service on a substitute basis, effectively an apprentice to the more senior clerks on his route.

On the train—its swaying, its unpredictable halting stops, the dim of the lamp light made dimmer still by the belching of the steam engine—clerks faced their ultimate trial. One veteran clerk recalled that the pride he felt in securing his position as a clerk dissipated on his first run:

I was dizzy and faint; the cars were dark with smoke and dust, and the whole scene inside seemed an endless tangle of pouches, sacks, and pigeonholes, presided over by a lot of perspiring demons, whose flying hands kept the air alive with packages and bundles, the while mumbling a jargon, probably concerning routes and connections, but which was all Fiji to me.

This clerk resisted the “impulse to resign instanter,” but others did not. The work itself was a screening device. But even those who remained on the job faced continual assessments. Because railway schedules and routes frequently changed, clerks in the service were examined every six months. Clerks dubbed the portable case the “sweat case”—and they frequently had their own with which to practice at home on their free time. The sweat case stood as a symbol of merit itself—impartial, dealing “honestly and justly with each man who comes before it,” and according “to every man the full meed [sic] of credit he deserves, just that and no more, and it exposes inefficiency and weakness,” in the words of one Republican postmaster.

Image 1: A clerk undertakes a “sweat case” examination, from Clark Ezra Carr, The Railway Mail Service, Its Origin and Development (1909).

The job was also the most dangerous in the civilian service. The Post Office leased railway mail cars from private railroad companies. These cars were old—usually refitted baggage cars—and made of wood, even as other cars had been upgraded to steel. Mail cars were located behind the steam engine; when wrecks occurred, mail cars were crushed “like a strawberry box.” And since oil lamps supplied the light by which the clerks did their work, flames engulfed the wooden cars after any wreck.

The threat of death pervaded the work, inviting analogies to military service. “Death or serious injury is a peril of duty as certain, if not so great, as a soldier to the army,” the Postmaster General’s annual report read in 1885. Advocating for Congressional passage of disability insurance specific to railway mail clerks, the report highlighted the duty the state owed to disabled clerks in language that would have been familiar to advocates of benefits for disabled Union veterans. “Reasonable care” ought to be “exercised by the Government for those on whom the misfortunes of its service strike hard.”

There was a lot of misfortune. Between 1887 and 1892, there were 1,610 injuries in the service and 41 deaths. The Postmaster General’s report on these casualties twinned the clerks’ sacrifice and service. There were train wrecks of varying severity nearly every single day of 1884. Most did not result in serious injury to clerks—or to the mail, whose delay or damage was also accounted for by the Post Office. But when they did, the juxtaposition of the clerk’s dedication to duty amidst injury evoked scenes of battlefield bravery. On December 26, 1884, a southbound Danville and Olney Railroad train derailed near Ste. Marie, Illinois, sending the mail car and passenger cars down an embankment. Clerk E.L. Pippin was pinned to a corner of the mail car and burned by the contents of a gas stove. He managed to extricate himself and rescue most of his mail. “His shoulder was badly bruised, neck badly burned, and hands considerably burned in his efforts to save the mail.” In 1903, the wreck of the Old 97—made famous by the numerous ballads it inspired—killed five clerks and injured scores more when a speeding mail train derailed on a trestle in Danville, Virginia.

The earliest efforts by clerks to organize grew out of a recognition of the job’s dangers. Railway mail clerks could not afford accident and life insurance. The Railway Mail Service Mutual Benefit Association (RMSBA) formed in 1874 to maintain a fund “for the benefit of members … who may become totally disabled, and for the widows, orphans, heirs, assignees, and legatees of deceased members.” It also was formed to improve “the condition of the employed” by influencing congressional legislation. That is, labor organizing in the railway mail service was aimed at securing better working conditions through the exercise of the right to petition government for the redress of grievance—in other words, to lobby Congress.

A broader print culture attuned to death on the rails aided the clerks’ cause. Even when membership numbers were in the low hundreds, the RMSBA held national conventions that attracted delegates—and media coverage—from around the United States. Railway accidents, frequently the subject of lurid newspaper accounts, also provided additional publicity for the Association—and for the personnel policies of the Post Office. For example, in 1887, seven postal clerks died in an accident on the Lake Shore Railroad in Goshen, Indiana. “The saddest part of it all is that the law requires that the pay of the mail clerk ceases the very day he is killed,” observed The Washington Post. One clerk’s widow was left “in destitute circumstances” as she was only able to obtain “the undrawn balance of her husband’s pay, about $50, the salary ending with the day of his death.”

By the last decade of the 19th century, the ranks of the railway mail service had grown as the service’s importance to mail delivery increased. In 1891, a new employee organization, the National Association of Railway Postal Clerks (which would change its name to the Railway Mail Association) formed as a vehicle to “perfect any movement that may be for their benefit as a class, or for the benefit of the Railway Mail Service.” Those two objects—the class interests of workers and the benefit of the RMS—were always in tension. But 15 years of repression by the Postal Department would cleave them fully, elevating dissident clerks to organizational leadership in the process.

Government Gags, Labor’s Grievance

Railways were required to deliver mail. Managers within the Railway Mail Service were therefore more familiar with labor unrest than other government officials. The “Great Railway Strike of 1877”—a turning point in the history of labor, capital, and state violence—was the first national strike as 100,000 railway workers and coal miners in multiple states ground commerce to a halt in response to wage cuts. At least 100 striking workers were killed in confrontations with national guardsmen, police, and Pinkertons. Although strikers generally made a point of allowing mail cars to pass, the unrest nevertheless slowed delivery. “Obstruction of the mails” would, in the Pullman Strike of 1894, soon become a pretext for federal intervention against striking workers, and form the basis of a federal criminal conspiracy charge against American Railway Union leader Eugene Debs. During that conflict, striking railway workers accused officials with the Atlantic Avenue Railroad, which had a contract with the Post Office, of illegally using U.S. mail signs on all of its railway cars in Brooklyn—even those that were not carrying the mail. By the end of the 19th century, the U.S. Railway Mail Service acted as a kind of scab wrapped in the flag. Indeed, it was rumored that the U.S. Postal Service insignia “are put on street car lines so that they can be filled with Federal bayonets to suppress strikers,” as an Arkansas Congressman observed in 1897.

But the letter carriers, postal office clerks, and railway mail clerks that comprised the rank and file of the Postal Department were also restive. As increasing numbers sought affiliation with both independent and Knights of Labor-affiliated associations, the Postal Department sought to literally mute their influence. In 1895, Postmaster General William Wilson, a Democrat and Grover Cleveland appointee, issued an order that sharply restricted the speech of postal employees:

Hereafter no Postmaster, Post-office Clerk, Letter Carrier, Railway Postal Clerk, or other postal employee, shall visit Washington, whether on leave with or without pay, for the purpose of influencing legislation before Congress.

Any such employee of the Postal Service who violates this order shall be liable to removal.

Postmasters and other employees of the Postal Service are paid by the Government for attending to the respective duties assigned them, which do not include efforts to secure legislation. That duty is assigned to the representatives of the people elected for that purpose.

If bills are introduced in either branch of Congress affecting the Postal Service, upon which any information or recommendation is desired, I am ready at all times to submit such as lies in my power and province.

This blunt expression of managerial prerogative was significant for several reasons. First, given the sheer size of the postal bureaucracy, the order represented the most significant curtailment of the speech of federal employees, an example of administrative constitutionalism in the breach. Secondly, the perceived necessity for the order suggested the threat with which the Department had come to view organized employee advocacy and Congressional solicitude. Finally, by emphasizing his own willingness to supply “any information or recommendation” to Congress, the Postmaster affirmed the hierarchy of the service—something Wilson believed needed shoring up as it seemed to him that clerks had “little other supervision than what was possible from army headquarters.” Politically appointed officials, not merit employees, were the only ones authorized to advocate before Congress. Although justified with reference to the bureaucratic goals of efficiency and organizational discipline, Wilson’s order ran counter to the core principles of the classified service: that a cadre of professionals would reduce the influence of politics in the bureaucracy.

The order was difficult to enforce. Its utility lay in the pretext that it gave superintendents for removing clerks—frequently for labor organizing. In 1897, the American Federation of Labor, which had come to supersede the Knights as the largest labor organization, denounced the “cruel, cunning, and systematic tyranny” of the post office for “preventing them from organizing like other employees.” The AFL, which had long advocated the inclusion of all postal workers in the federal eight-hour day rule, also demanded that clerks outside the railway mail service be classified within the civil service, illustrating the symbiotic relationship between organized labor and civil service reform. The following year, the Federation explicitly invited postal workers to organize and affiliate. “In view of the efforts made by the trade unionists of this country to protect the interests of the post office employes [sic],” the organization resolved at its 1898 convention, “we suggest the advisability of those employes [sic] joining the trade union movement, and to thus render by their affiliation with us a just return of service to other wage-workers.” This formulation suggested precisely what the Post Office Department knew to be true: if affiliated with an increasingly formidable AFL, postal workers—numerous, popular, and politically connected—could extract concessions from the Department.

Far from creating employees that deferred to supervisors, proclamations by the Department catalyzed efforts to organize. In 1900, the AFL resolved to “appoint a representative” to attend the annual postal clerk convention to “endeavor to have them affiliate with the American Federation of Labor.” Although the branches of the postal service were divided along occupational lines (hampering overall postal worker strength), hardship in one part of the service spilled over to others. For example, post office clerks were paid less than letter carriers or railway mail workers—and the wage scale for all clerical grades of the federal workforce were unchanged since 1854. As a result, there were serious labor shortages and slowdowns in places with high costs of living and high volumes of mail. In New York and Chicago, railway mail clerks were called in to work as postal clerks during their rest periods.

For the AFL, the affiliation of postal workers was strategically significant in vindicating labor’s vision of “the right of agitation.” Long before the Post Office initiated its notorious censorship campaign against radicals during the First World War, it suppressed trade union publications and denied some labor publications second-class rates—an expensive penalty. Since the Supreme Court’s 1878 ruling in Ex Parte Jackson—which held that the First Amendment did not apply to the mails, affirming the reach of the Comstock Act—it was clear that the route of censorship ran right through the Post Office. Wilson’s order was, of course, noxious to postal employees. But it also sent an ominous signal to a labor movement that, in AFL President Gompers’ words, “stood for the fullest freedom of speech and of the press.”

Four months after Roosevelt’s surprise assumption of the presidency, he issued Executive Order 163, known derisively as the “Gag Order”:

All officers and employees of the United States of every description serving in or under any of the Executive Departments and whether so serving in or out of Washington are hereby forbidden either direct or indirect, individually or through associations, to solicit an increase of pay, or to influence or attempt to influence in their own interest any other legislation whatever, either before Congress or its Committees, or in any way save through the heads of the Departments in or under which they serve, on penalty of dismissal from the government service.”

Whereas the Postmaster General’s 1895 order applied only to postal workers, Roosevelt’s order applied to all federal employees. Public servants could not seek redress—or simply share information—before Congress. Nor could their “associations”—a reference to unions. But individuals were required to testify to the Civil Service Commission upon request. And, per another 1902 executive order, merit employees could be removed for any cause (other than race or religion) if a supervisor believed removal would “promote the efficiency of the service.” Such removals did not require the right of a hearing before the Civil Service Commission. Previous rules had required supervisors to submit “reasons given in writing” in order to allow the dismissed employee to make a “proper answer.” Executive department heads held unchecked power to dismiss, and a revision to the gag order brought still more federal employees under its mandate to speak to Congress only through those same department heads. By routing all complaint through management, these civil service reforms foreclosed the possibility of denouncing working conditions or management themselves. “I did not usurp power,” Roosevelt later put it in his autobiography. “But I did greatly broaden the use of executive power.” In so doing, he “molded the merit civil service into an instrument of executive-centered government,” in the words of scholar Steven Skowronek.

For much of the federal workforce, Roosevelt’s breathtaking vision of presidential power came as a diminution of their own rights and privileges. Roosevelt had been, in his own words, “ever a most zealous believer in the merit system,” championing civil service reform while a State Assembly member in New York, and serving on the U.S. Civil Service Commission from 1889 to 1895—an experience that impressed upon him that “the bulk of government is not legislation but administration.”

Roosevelt’s presidential appointments belie idealized notions of an apolitical bureaucracy. His first Cabinet appointment was the position of Postmaster General, which he bestowed upon a political ally, who initiated a sprawling investigation of abuses, fraud, and favoritism within the Department. Rather than taking politics out of the bureaucracy, it enabled him to use the bureaucracy to achieve political ends. Indeed, Roosevelt believed that the executive branch was best suited to quick, decisive action, “limited only by specific restrictions and prohibitions appearing in the Constitution or imposed by the Congress under its constitutional powers.” As chief executive, Roosevelt believed he should act “unless such action was forbidden by Constitution or by the laws.” Civil servants—competent, obedient, meritorious—were part of the organized machinery of the executive branch, where the president stood towering atop. Under Roosevelt’s stewardship theory of the office, “it was not only his right but his duty to do anything that the needs of the [n]ation demanded.”

The phrase that postal workers and organized labor attached to Roosevelt’s orders— “gag rules”—should not pass by without comment. As Daniel Carpenter, Maggie Blackhawk, and Kate Masur have all recently argued, petitioning was a crucial feature of 19th century democracy—an expressive tool for conveying grievance, as well as an organizational device that induced individuals to organize their claims collectively. They were, quite frequently, a political tool for the dispossessed—a way for women and men excluded from electoral politics, political debates, and even from citizenship itself to change the course of public debate. Irate at the flood of anti-slavery petitions (frequently signed by women and people of color), pro-slavery Congressmen adopted a rule prohibiting their chamber from entertaining any petition calling for abolition. This original “gag rule” produced its own unintended consequences, triggering a massive and transformative anti-slavery petitioning campaign that expanded the scope of the anti-slavery debate while portraying slavery’s defenders as anti-republican.

Even the oldest railway mail clerks would have been too young to remember this history firsthand. But as Richard Johns has argued, the postal system, a conduit for the dissemination of abolitionist literature and an emblem of federal power, was central to debates over slavery in the public sphere. In the antebellum period and in the early 19th century, the Post Office pursued censorship. Analogies to slavery came easily to the labor movement—indeed, denunciations of “wage slavery,” “white slavery,” and, later, “sweatshop slavery,” was the rhetoric by which “the white worker was made,” according to labor historian David Roediger. Like the denunciations of antebellum censorship, the “gag order” of the early 20th century expressed the same moral indignation and implication of tyranny.

The AFL’s response to Roosevelt’s orders revealed the continued rhetorical power of labor republicanism, insisting that federal service ought not be tantamount to second-class citizenship. At its 1905 convention, the organization observed a tendency “in certain newspaper and official circles” to restrict the organizing and speech rights of public employees. Public employees ought to “retain all the rights of citizenship, among which are the right to organize for political or legislative purposes”—a direct challenge to Roosevelt’s orders. As one delegate from the International Seaman’s Union proclaimed, public workers “shall be as free in the exercise of their rights as are the employes [sic] of a private corporation or individual.” After all, “the government is as liable to err on the side of injustice to its employes [sic] as any other employer in the absence of the power to organized.” As the power and presence of the government expanded, it was imperative that public workers assert these rights. “With that extension of governmental functions goes the right of the employe [sic] to retain his rights as a citizen, both political and economic.”

Bureaucratic centralization illustrated the necessity of worker organizations. In March of 1906, Gompers presented Roosevelt and Speaker of the House Joseph Cannon a “Bill of Grievances.” The letter, addressed to “All trade unionists of America,” was meant to announce the AFL’s entry into politics. The Federation urged members to vote against officeholders unfriendly to labor issues. In 1906, labor had much to grieve: the perversion of the Antitrust Act, the use of the judicial injunction, Lochner, the lack of appointments of unionmen to the House Committee on Labor. But it was Roosevelt’s gag order that occupied the final, most significant spot in the litany. “The constitutional right of citizens to petition must be surrendered by the Government employe [sic] in order that he may obtain or retain his employment.”

As bad as this constitutional abrogation was, the signal sent by Roosevelt’s centralization was still worse. In August 1906, the Postal Department issued its own orders consistent with the president’s theory of executive power. It forbade postal employees from discussing working conditions publicly at all.

It is deemed essential to the proper administration of public business that officers and employees of this office shall maintain respectful relations with railroad companies and other carrying companies as well as with their superior officers. Railway postal clerks must not engage in controversies with or criticisms of railroad officials involving the administration of the postal service by furnishing information to newspapers or publicly discussing or denouncing the acts or omissions of such officials as affecting the postal service.

Clerks who created “controversies” through their criticism would be “subject to discipline and possible removal from the service.” The Postal Department intended to keep obscure whatever “acts of omission” may have been undertaken by the railroads. Clerks looking to convey their “personal knowledge” for the “betterment of the postal service and the comfort and safety of their persons” could only do so through their superior officers. Though the order was itself indication of the Department’s disinterest in the clerks’ “personal knowledge.” Indeed, a railway clerk in Texas dutifully wrote to his division superior regarding an incident in which his fellow clerk was killed on a car that was known to be unsafe. He was told that the Department did not control car construction and that men who “did not care to assume the necessary risks had no place in the Railway Mail Service.”

Roosevelt’s departure from office did not devolve authority from the executive hierarchy. Shortly after he was inaugurated, William Taft expanded on Roosevelt’s orders by prohibiting federal employees from responding to Congressional requests for information. Such information could only be furnished by department heads. The administration explained the rule as one of rationalization: it was simply more efficient to centralize authority in the heads of departments. At the same time, Taft’s Postmaster General imposed an order known as the “wreck gag,” which prohibited employees from making any public comments on railway accidents or saying anything which might disturb the Department’s “respectful relations with the railroads.”

Protesting the Gag

The gag order radicalized elements of the railway mail service. Postal officials harassed, reassigned, or fired leadership that defied the gag order. This dynamic not only encouraged further rebellion, but, since fired workers were no longer beholden to a mandate of silence, created a political movement around the speech rights of workers. Congress, intentionally sidelined by Roosevelt’s vision of the executive, was instrumental in the fight to enshrine the right of public employees to disclose information to Congress. Congress was, after all, also bound by the gag order as the right to petition carries with it a correlative duty to hear. Executive branch orders not only gagged workers. They deafened Congress.

Urban Walter’s Harpoon was the most colorful and widely disseminated publication launched in opposition to the gag orders. But it was not the only one. In 1909, postal clerks in Seattle published the Post Office Bundy Recorder, which bore the motto: “For Freedom and for Equal Laws”—an assertion of free speech parity between post office workers and other citizens. Satire was the Recorder’spreferred mode of critique. Each issue contained a column called “He Criticized the Administration.” Quoting verbatim from Civil Service Commission reports on removals for “political activity,” the journal interjected every few paragraphs: “He Criticized the Administration! Think of it! He Criticized the Administration!” After a few months’ publication, the paper’s editor received a note from a Post Office Inspector. “You are hereby allowed three days to show cause why you should not be removed from the Postal Service for insubordination, disrespect to your superior officers, and for inciting, or intending to incite discontent and disorganization among your fellow employees.” The inspector had taken issue with the fact that the Recorder urged its readership to subscribe to the Harpoon. The editor was removed from the service.

The official response to a print culture of defiance stoked further opposition. In early 1911, Walter issued a special “anti-gag” bulletin between regular issues of the Harpoon. Its purpose was to draw attention to Postmaster General Hitchcock’s refusal to lift the “wreck gag” even as the House contemplated a law that would require the replacement of wooden mail cars with safer ones made of steel. Walter sent the circular in envelopes that were intercepted by postal inspectors in Denver.

Walter was arrested and charged with violation of postal laws, and was instructed to remove the objectionable passages. He compiled with a black ribbon—and, not one for subtlety, he announced the presence of “Censored Matter Inside.” The matter inside also included his story of arrest—a prelude to the record 200,000-copy print run of the Harpoon’s next regular issue.

As postal authorities waged war upon the written word, they also intensified their search for “secret societies” and “pernicious activity” within the service—in other words, unions. Joseph Stewart, the Second Assistant Postmaster General, told division chiefs to instruct their employees that “it is incompatible that they should assume another oath with a secret organization in the service which may at any time interfere with the obligations which they have assumed upon entering the service.” The Postal Department already employed a cadre of inspectors responsible for interdicting obscene and “filthy” matter—the most famous of whom was Anthony Comstock himself. Inspectors opened the mail of clerks suspected of organizing the AFL-affiliated Railway Mail Clerks’ Protective Association and the Brotherhood of Railway Postal Clerks, a progressive, breakaway faction of the Railway Mail Association that was supported by the Harpoon. The purpose of Stewart’s order was to chill organizing outside of the Department-dominated RMA.

More direct pressure was brought to bear upon clerks that sought independent organization. Supervisors summoned clerks for “inquisitions.” One clerk in St. Paul was told by his superintendent that, as per Stewart’s order, he had to withdraw from the Brotherhood. The clerk told his superior that he “had a clear idea of my duty in that regard and besides had good sound legal advice to the effect that the Post Office Department had no right to prohibit us from organizing.” The superintendent informed the clerk that “anyone who takes such a stand against the department is liable to get hurt, and you’ll have no kick coming.” Other times, the threats weren’t so veiled. George Nichols, a railway mail clerk with 22 years of experience, was questioned multiple times by his supervisors about his membership in a “Clerks’ Protective Association.” At first, Nichols declined to answer the questions posed to him. But on a second round of examination, he admitted his membership and was removed for “conduct detrimental to the welfare of the service.”

Those who sought reform within the Railway Mail Association were also not spared. In early 1911, Carl Van Dyke was demoted for “having been perniciously active in endeavoring to foment discontent on the part of fellow employees” and therefore exerting “an influence detrimental to the best interests of the service and tending to insubordination.” Van Dyke resigned from the service and was immediately elected as a chairman of the RMA—an indication of the widespread unpopularity of Departmental orders. Van Dyke, it seems, had a talent for electoral politics. After unseating a nine-term incumbent, Van Dyke was elected to Congress as a Democrat in 1914, where he served until his sudden death in 1919.

The divisions between insurgents and the department-aligned conservatives in the RMA made the former even more vulnerable. RMA regulars weaponized the postal bureaucracy against their organizational rivals. In New England, these rifts attracted widespread media attention. In Boston, Charles Quackenbush, a railway mail clerk, was discharged for “disloyalty” and “disposition to create strife” in the spring of 1911. Quackenbush had run for the presidency of a division association within the RMA on a platform antagonistic to the Postal Department—namely, an end to the gag rules and the suggestion that the Harpoon be made the official organ of the RMA. Perhaps the most grievous charge against Quackenbush was that he met with AFL organizers “on March 12 in the rooms of the Federation in Boston.” Quackenbush’s rival, the incumbent divisional president and avowed foe of the AFL, reported these activities to the regional inspector, Lawrence Leatherman.

This shadowy description of Quackenbush’s activities was in keeping with the Post Office’s conspiratorial attitude toward unions—indeed, the Department engaged in the very secrecy and subterfuge that it accused the AFL of evincing. Leatherman hunted for stains on Quackenbush’s record. To the chagrin of the Department, Quackenbush, a 12-year veteran of the service, had received excellent performance reviews—so excellent, in fact, that the Boston superintendent (and Quackenbush’s direct superior) wondered how he should respond to Quackenbush’s request to understand the reasons for his removal. “Case examinations, 93; work in car, 94, habits, 95; attendance, 95; application, 93; ability in present grade, 93; general merit, 94; health 95.” Indeed, many of Quackenbush’s fellow clerks responded with dismay at his discharge. The railway mail clerks “feel sure there has been a gross mistake or misrepresentation made somewhere,” explained one in a missive to Postmaster General Hitchcock. Despite the outcry from the rank-and-file (or, as Leatherman put it, “the more hot-headed railway postal clerks”), the Department stood behind the discharge because it was believed to repress organizing. “It will have a very beneficial effect upon the remaining clerks, who, believing themselves protected by their organization, took upon themselves the position of dictators and critics of the department and the honorable Postmaster General.”

The Department’s hope for a quiet resolution to the episode were quickly dashed—a reflection of the AFL’s savvy use of publicity. The Boston Globe and the Boston Evening Transcript ran articles about Quackenbush’s firing the day it occurred—an event framed as the result of a dispute between warring factions within the RMA. The “great surprise” that awaited Quackenbush even caught his boss off guard—and more than a little baffled. “All I know is that I have received instructions to drop Mr. Quackenbush and I shall carry them out. I shall notify him today. That is all I can say.” Other regional newspapers reported on both the firing—and the fact that despite it, Quackenbush resoundingly defeated his rival for the presidency of the New England division of the Railway Mail Service.

The Department’s investigation not only installed the “dictators and critics” at the helm of the RMA; it also occasioned unwanted Congressional scrutiny into the affair. In response to press reports and constituent protest, Massachusetts Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge, Connecticut Sen. Frank Brandegee, and Connecticut Rep. Thomas Reilly requested more information into the clerk’s dismissal. In May of 1912, the resulting 265-page report was published. It detailed the Department’s use of the inspectorate to generate a pretext for Quackenbush’s removal, its network of informants, its attention to adverse publicity, and, most strikingly, its aversion to Congressional oversight. For example, one Boston-based inspector forwarded Leatherman a questionnaire that Sen. Robert M. La Follette had sent to all the railway mail clerks. The inspector promised to keep digging into who responded to La Follette’s invitation to defiance. “It is very hard to get any of these clerks to talk,” Leatherman groused to the Chief Inspector in Washington. “But I think I know of one more who will.” The identity of that would-be informant is lost to history. Several days later, President Taft issued a new order:

Having considered the written arguments for and against the application for reinstatement of Charles H. Quackenbush in the Railway Mail Service, and having reached a conclusion that the offense for which Mr. Quackenbush was removed does not merit more of a penalty than a suspension without pay for a year, and that such penalty has been satisfied, I hereby direct that Mr. Quackenbush may be reinstated in the Railway Mail Service without reference to the provisions of the civil-service rule governing reinstatements.

Quackenbush was back on the job.

Congress and the Gag

Taft’s order suggested the political success of the anti-gag campaign—a campaign that he had strongly opposed just a year earlier. In a 1911 speech before the Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen, the president couched his opposition to AFL-affiliation for government employees in the rights/privileges distinction. “The government employees are a privileged class whose work is necessary to carry on the government and upon whose entry into the government service it is entirely reasonable to impose conditions that it should not and ought not to be imposed upon those who serve private employers.” Taft’s about-face on the severity of Quackenbush’s offense—fomenting dissent by seeking affiliation with the AFL—is perhaps less striking than the president’s apparent disavowal of the executive branch authority he had so recently claimed. In late 1911, Taft issued an executive order that amended civil service rules, providing greater procedure for the discharged employee and thereby inching the civil service further from the at-will model. While federal workers could still be fired to “improve the efficiency of the service,” the worker had to be “furnished with a statement of reasons and be allowed a reasonable time for personally answering such reasons in writing.” These procedures were minimal and did nothing to diminish the power of executive branch officials who wanted to discharge a disagreeable employee. But they nevertheless implied the kind of adversarial procedure that might allow a discharged employee to make his case outside of the executive branch. A few months later, Taft issued an order superseding Roosevelt’s of 1906 and his own of 1909. Whereas these previous orders involving federal employees had been framed negatively—“it is hereby ordered that no … subordinate in any department of the Government … shall apply to either House of Congress … nor shall any such person respond to any request for information … except through…the head of his department” —Taft’s new order emphasized the affirmative duty of department officials to communicate employee speech to congress:

It is hereby ordered that petitions or other communications regarding public business addressed to the Congress or either House or any committee … by officers and employees in the civil service of the United States shall be transmitted through the heads of their respective departments or offices, who shall forward them without delay, with such comment as they may deem requisite in the public interest.

With its emphasis on the speedy transmission of “communications regarding public business,” Taft’s order suggested that the public had an urgent interest in the urgent and significant information that civil servants may have acquired on the job—a turnabout that highlights the malleable nature of arguments for efficiency.

Taft’s newfound solicitude for the speech and employment interests of the civil service was prompted by Congressional attention—attention stoked by pressure from the AFL. La Follette’s mass survey of the nation’s 15,000 railway mail clerks publicized the very same day as Taft’s emendation of the gag orders and just days after Quackenbush’s dismissal. “The railway mail clerks have the right to organize,” La Follette announced in a preface to the survey. “If the officers of the department are endeavoring to prevent them from so doing by threats of discharge, such action is without legal authority or moral right.” The results of the survey would, according to La Follette, determine the shape of the legislation he promised to introduce. La Follette promised to “do everything in my power” to secure a bill that guaranteed “to all government employees the right of petition which belongs to every citizen, and the right to form or join labor organizations for the improvement of their conditions.” The survey’s first three questions concerned whether or not the Post Office had pressured clerks to “cease your activities in the Federation.”

Before La Follette had time to assess the degree of repression in the Service, Samuel Gompers had persuaded the House Committee on Reform in the Civil Service to hold hearings on the AFL-sponsored legislation that would become the Lloyd-La Follette Act. Gompers decried “the denial to Government employees of the rights guaranteed to them by the Constitution of our country to petition the Congress.” Gompers’s language was that of labor republicanism—the belief that democracy (and moral virtue) required an economically and politically independent citizenry. “The commonest criminal in all our country, the murderer, the ravisher of the innocent convicted of the most heinous offense known to our laws may petition the Government or any branch of it in any matter in which he believes his rights and liberties are affected, but a man or woman being appointed as a Government appointee … is denied the right of petition.” Worse still, from Gompers’s perspective, was the fact that the Postal Office forbade RMS clerks from belonging to any “secret societies,” a cryptically derogatory term for unions. For Gompers, this denial of association was as significant as the denial of the right to petition, for not only did it undermine the purpose of the union, it also foisted a “stigma” upon the AFL, which, in turn, encouraged “private employers [to] take the cue and … redouble the antagonism.” The hearings amply proved Gompers’ latter point. James Emery, of the National Association of Manufacturers, testified in opposition to the bill.

The House Committee accepted Gompers’s framing and subjected Joseph Stewart, the Second Assistant Postmaster General who had promulgated the anti-association order, to withering questioning. “Does not the Constitution giving the right to petition to all the people create a civil right?” asked Congressman Wilson. “The right of petition is inherent in our form of government,” replied Stewart. “Would the acceptance of civil employment with the Government destroy that civil right?” the Congressman replied. No, Stewart explained: “They can petition Congress in the service just as well as out of the service, and the only restriction placed upon them is that they shall send the petition to the head of the department in order that it may be transmitted.” Not satisfied with this answer, Congressman Kendall pushed further. “There would not be a complete right of petition left if some man intervened?” Stewart thought the right remained intact. “But, supposing that his superior officer suppresses his request,” queried Congressman Boehne, “what is left for the employee after that?” What was left, Stewart replied, was the discretion of the executive. “When a man enters the service and becomes a part of a branch of Government he owes as certain duty to which his ordinary rights and privileges become subordinated, and he can hardly claim for himself all the privileges that he might exercise if he remains outside the civil service.”

For Congress, the mediating influence of the executive was an even greater evil than the subordination of ordinary rights and privileges. Taft’s sweeping 1909 order forbade civil servants from “respond[ing] to any request for information from either House of Congress …. except through, or as authorized by, the head of his department.” Frank Morrison, the AFL’s secretary and a frequent advocate before Congress, emphasized that the gag rule curtailed Congress’ capacity to gather information and represent their constituencies. “There are certain conditions that the railway mail clerks want,” Morrison explained. “The department wants to continue the clerks in wooden cars, where the clerks take the chance of being killed, and the employees are anxious to have steel cars.” The Postal Department’s 1906 “wreck gag” and Taft’s order had not only muted Congressional cognizance of these conditions, but had also left Congress unable to account for the fees it paid to the railroads for use of the wooden mail cars. This charge of corruption had special potency as reformers in both parties sought to claim the mantle of progressivism—enlisting civil servants as guardians of the public fisc a notoriously spoils-ridden agency. “I do not say this in a captious spirit, but the Government is paying for everything it gets, and some people think it is paying too much,” Morrison told the committee. “An investigation would probably show if it is paying too much.” The suggestion that civil servant communication with Congress might disclose otherwise undetectable frauds would, more than half a century later, become a primary accountability and taxpayer-centric justification for whistleblower protections.

Stewart was questioned directly about the gag rule’s effect on Congress’ ability to consider legislation affecting steel cars. “There is an impression that the President attempted to limit the action of Congressmen,” Stewart explained. “That is entirely incorrect. There is absolutely nothing in the wording of the order or in its intention to place any limitation upon the legislative.” The postmaster’s attempts to clear up the “misapprehension that exists in the minds of Congressmen” failed. After two days of testy exchanges with Stewart, the committee, in defense of legislative prerogative, had resolved to “provide by statute that a postal clerk who shall apply to Congress for legislative relief shall not be discharged on that account.”

Carl Van Dyke, the clerk discharged for fomenting discontent and subsequently elected to leadership in the Railway Mail Association, testified in retort to Stewart. He expounded on the manifold grievances that existed in the service: long hours, “poorly constructed, poorly lighted, unsanitary and dangerous wooden cars,” unfilled promotions, inadequate compensation, arbitrary demerits, and, most significantly, antagonism and distrust between clerks and postal officials. Van Dyke’s very presence, however, was conditional upon his discharge—a fact that he emphasized at the outset. “If I were looking for reinstatement to the service, I would not dare to come before this committee and make the statements I intend to make to-day.” He fashioned himself as a truthteller—not because of any superior virtue but because an outsider status was foisted upon him by his dismissal. It was this outsider status that allowed him to read into the record numerous letters authored by clerks portraying the dismal conditions of their cars—letters that occasioned their own dismissals. And it was only from Van Dyke that the committee learned of the response that awaited a clerk as he reported the conditions of his car up the chain of command, as the regulations required. “Everything seems to indicate that you are making exaggerated reports about the condition of mail cars you work in and I suggest it would be advisable for you to be a little more conservative,” the St. Paul Superintendent of the Railway Mail Service responded to one letter. “A Mail car is a workshop, not a drawing room or a parlor.”

Enforced silence created conditions under which corruption could take root. The superintendent’s information on both the clerk and the car had been furnished by an employee of the Great Northern Railway, with which the Post Office contracted for use of the wooden mail cars. The clerk—who “has given us trouble in the past,” according to the Great Northern—was fired. These incidents prompted Van Dyke to invert Holmes’ axiom. “It seems to me that inasmuch as these men are employees of the public that … they should be required to make such reports, so as to help ensure the safety of the traveling public, instead of being disciplined for giving information which they are in the position to obtain.” Advocates like Van Dyke imagined a world in which public employment obligated rather than forbade speech. It was an acknowledgment of the special value of public employee speech.

Robert La Follette introduced the AFL-sponsored legislation in the Senate. The questionnaire he mailed to 15,000 railway mail clerks made him something of an authority on the problems of the service. In his letter to the clerks, La Follette sought information about the effects of the gag order, but also any “intimidation” to “prevent you from joining or to force you to withdraw from a union.” The responses revealed “the fact that the conditions in this service are probably more arbitrary than in any other branch of the civil service.” He learned of clerks fired for organizing, or merely meeting with organizers. He discovered dismissals for giving “publicity to unsanitary conditions”—conditions that, at least in the opinion of the superintendent of the Chicago Tuberculosis Institute, would have been criminal had they existed in the private sector. “Many cases of consumption among the clerks have been brought to my attention and I have no hesitancy in saying that in most instance they are directly traceable to the conditions under which the men are forced to work.” Four Chicago clerks died of tuberculosis likely contracted in the course of their employment. And the clerk who publicized conditions in Chicago was dismissed. Tuberculosis, no less than train wrecks or corrupt railcar contracts, was a matter of the public interest about which postal workers had firsthand information. La Follette had his own firsthand brush with Postal Department repression. “My mail was subjected to an espionage that was almost Russian in its character,” he proclaimed, brandishing a package of opened envelopes on the Senate floor.

But La Follette also asserted that executive branch prohibitions on civil servant speech and organizing ran counter to the principles of a merit-based civil service, turning executive-centric arguments for efficiency on their head. La Follette speculated that the Post Office’s desire to quelch AFL-affiliated organizing was not only because it wanted to bury grievance, but also because an institution that represented workers would not provide departmental supervisors the adulation they craved. Employer-dominated associations carry with them “political prestige”—they hold conventions at which “the Postmaster General or his representative is present, and as a result there is always a laudatory resolution passed expressing the gratification of the particular organization with the administration of the department and expressing confidence in the official who is present representing the administration.” Such occasions amounted to free advertising for the party in power “in the political campaigns which follow.” Prohibitions on the unions thus made a mockery of the merit system, turning conventions of classified employees into rallies for the current administration. La Follette, an insurgent Republican and rival of the party’s Old Guard, was, at the time, challenging Taft for the primary nomination. A progressive leader in the Senate but an enemy of the president, La Follette may have been especially sensitive to executive branch manipulation of the civil service.

The Lloyd-La Follette Act was signed into law as a part of the postal appropriations bill for 1913. The Act specified procedures for removal and demotion, requiring written notice and a right to reply, but explicitly did not require any examination of witnesses or trial-type hearing. It announced “the right of persons employed in the civil service … to petition Congress” or to “furnish information to either house of Congress, any committee or any member thereof.” Such a right “shall not be denied or interfered with”—implicating the previous requirement to lodge a grievance with a departmental head had abrogated the speech rights of civil servants. Finally, it announced that “membership in any society, association, club, or other form of organization of postal employees … shall not constitute or be cause for reduction in rank or compensation or removal of such person or groups of person from said service.”

At the same time, the Act explicitly denied the right of federal workers to strike—an acknowledgment of the potency of a misinformation campaign waged by Postal Department officials. Raising the specter of a strike by postal workers—a strike that ground business to a halt when it was eventually undertaken by New York City letter carriers six decades later—Department brass hoped to turn public opinion against postal workers. However, the AFL readily assented to a no-strike provision—a concession to political reality. Samuel Gompers helped to craft it in consultation with the amendment’s Senate sponsor, Missouri Democrat James Reed. The AFL’s federated structure supplied a ready rejoinder to such scaremongering as the Federation granted complete autonomy to national affiliates. Indeed, this federated structure may have been the reason that the AFL so readily assented to, and even authored, the no-strike provision: it did not threaten the core organizing model of the AFL while underscoring the organization’s respectability. Affiliate unions had autonomy, and the AFL itself could not compel a strike. The Union Postal Clerk proudly touted the passage of the Act as a “complete victory,” and emphasized (in all-capital lettering) that “legislation is the last recourse of public employes in the settlement of grievances—not strike.” Today it is accepted as doctrine that public sector employees lack a First Amendment right to bargain and strike—a fact that, as Kate Andrias observes in her contribution to this essay series, the Supreme Court has tended to assert without explanation. This absence of judicial reasoning was made easier by the AFL’s own rejection of the strike for public employees at the very moment when their statutory right to associate was created.

“Postal Clerks Win” blared the headline in The Washington Post. This assessment was accurate, if incomplete. The AFL had won as well, having written the legislation and approved its only significant amendment: a prohibition on affiliation with organizations “imposing an obligation or duty upon them to engage in any strike.” The American Federationistreported that Gompers appeared before the Committee on Post Roads and “made a very lengthy and exhaustive” argument on behalf of the anti-gag legislation. In vindication of the AFL’s 1906 Bill of Grievances, “the relief sought has been secured.” In ensuring the right of public employees to speak or petition without fear of reprisal, Congress spoke the language labor republicanism—a rhetoric that elevated the speech of civil servants into a core emblem of citizenship. “I know of nothing in the nature of our institutions that makes a man who enters into the civil service of the United States a slave,” proclaimed Mississippi Sen. John Sharp Williams. The “despicable gag rule” represented “a denial to the men themselves of not only a constitutional but a natural right,” in the words of Senator Reed. The Constitution “does not make an exception of citizens who happen to be in service of the government,” proclaimed an issue of La Follette’s Weekly, inserted into the record by Henry Ashurst, a Democratic senator from Arizona. “It does not say that all people may petition the Government, except, for instance, the railway mail clerks.”

The Act effectively repealed two decades of gag orders and at the same time asserted Congress’ interest in overseeing the executive branch and the civil service. It also prompted a flurry of organizing. After its passage, the Brotherhood of Railway Postal Clerks—the insurgent faction of the RMA—affiliated with the AFL. Urban Walter’s Harpoon became its official organ. In 1917, the AFL chartered the conservative (and, by then, whites-only) RMA as an affiliate. By the end of the decade, all branches of the postal service—letter carriers, rural carriers, postal clerks—were affiliated to some degree with the AFL.

That three institutional interests— those of the clerks, Congress, and organized labor— were braided together under the banner of free speech is not a mere artifact of the political ferment of the early 20th century. Rather, safeguarding the speech and association rights of civil servants was understood as a precondition to democratic accountability. Deeply distrustful of state institutions and as sensitive to the political value of publicity, organized labor was central to articulating the transparency and accountability dimensions to civil servant speech. The Postal Department’s brazen repression of both labor organizing and the disclosure of information about workplace conditions proved the necessity of independent and organized worker power. Free speech was thus both a precondition to and a result of labor organizing. Statutory protections for whistleblowing by government workers originated in the death toll of the wrecked mail car, in the tubercular post offices of the early 20th century, and in the dismissals of clerks who spoke publicly about these conditions. A labor history of public employee speech illuminates how substantive democratic accountability can be fashioned from workplace grievance, and how contemporary whistleblowing originated in collective struggles over power at the public worksite rather than the dictates of individual conscience. This history suggests that laws that strengthen the rights of all public sector workers may prove to be the best sort of whistleblower protections.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Sam Lebovic, Katy Glenn Bass, and the Knight Institute for organizing the workshop from which this paper emerged. I am grateful to symposium participants and to Reuel Schiller for their helpful feedback.

© 2024, Sarah Milov.

Cite as: Sarah Milov, Gags and Grievance: The Labor Origins of Whistleblowing, 24-18 Knight First Amend. Inst. (Oct. 28, 2024), https://knightcolumbia.org/content/gags-and-grievance-the-labor-origins-of-whistleblowing[https://perma.cc/5NGC-ETPK].

“One Man, Fighting Alone, Defies Strong Arm of P.O. Department,” Tacoma Times, July 1, 1909, 8.

Figures from Hearings: House Committee on Post Offices and Post Roads. Post Office Appropriations Bill for 1912 (1910), 310-311.

William Jefferson Dennis, Traveling Post Office: History and Incidents of the Railway Mail Service (Des Moines, 1916), 63–64.

Bryant Alden Long, Mail by Rail: The Story of the Postal Transportation Service, (New York, 1951), 144–45. According to Walter, more than 10,000 of the 16,500 men in the service subscribed by 1911. Circulation estimates from Post Office Appropriation Bill, 1913: Hearings before Subcommittee No. 1 of the Committee on the Post Office and Post Roads, House of Representatives, 62nd Cong., 2nd sess., January 1912.

Statement of Samuel Gompers, President of the American Federation of Labor, in Removal of Employees in the Classified Civil Service: Hearings before the Committee on Reform in the Civil Service on H.R. 5970, House of Representatives, 62nd Cong., 1st and 2nd sess., April 20, 1911, 4.

Lloyd-La Follette Act of 1912 5 U.S.C. § 7211.

Charles J. Coleman, “The Civil Service Reform Act of 1978: Its Meaning and Its Roots,” Labor Law Journal, April 1980, 200–01; U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board, “Merit System Principle 9: Whistleblower Protection,” https://www.mspb.gov/msp/msp9.htm. United States Government Accountability Office; “Whistleblowers: Key Practices for Congress to Consider When Receiving and Referring Information,” May 2019, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-19-432.pdf.

McAuliffe v. New Bedford, 155 Mass 216 (1892).